Flushing Mortgage Payments Down the Toilet

Nobody likes to pay rent. You never see that money again. From the point of view of the renter, paying rent is just like flushing your money down the toilet. The money is gone.

Many proud home owners live under the impression that they do not flush their money down the toilet each month. Unfortunately, that is not entirely true. Most home owners have to make monthly mortgage payments. Part of these payments does pay for the house, but another part pays for interest on the debt. Paying interest on debt is very similar to paying for rent. The money is gone, you will never see it again. To find out how much of your mortgage payments will be flushed down the toilet each month, we need to do some calculations.

Buying a house is a highly leveraged and, therefore, risky bet. Buying a property with a 20% down payment is a bet with 5× leverage. An 8% decrease in the value of the home means that the home owner just lost 5×8 = 40% of his down payment! The calculations that follow should be considered in conjunction with changes in home value or when home prices are expected to remain stable over the long run.

How much interest are you paying?

As you pay your mortgage, how much is owed to the bank decreases with time. The home owner only pays interest on the remaining balance, not the whole amount borrowed.

To illustrate this point consider a simple mortgage payment scheme with decreasing payments. Assume you borrow $500,000 from your bank at an interest rate of 5% per year (or 0.407% per month) for 25 years (300 months). One way to pay down the mortgage debt is to pay, each month, a fixed part of your total debt and all interest accrued during that period. If you choose to pay your mortgage in 25 years (300 months), then at each month you pay 1/300th of the initial balance of $500,000 and all the interest accrued during that same month. This way, any interest owed never compounds for more than a month. If the amount initially borrowed is $500,000, then the amount of principal paid each month is

$500,000/(300 payments) = $1,666.67 per month.

The interest accrued during the first period is

500,000 × 0.00407 = $2,037.06.

So, the first month’s payment is

1,666.67 + 2.037.06 = $3,703.73

You owe an initial balance \(B_{0}\) of $500,000 when you take out the money. After you make your first payment, at the end of your first month, you will owe

\(B_{1}\) = 299/300 × 500,000 = $498,333.33

At the end of the second month, you will again pay $1,666.67 corresponding to 1/300th of the principal, but this time your remaining balance has decreased to $498,333 and so you will pay a little less interest. The total payment at the end of the second month is given by

1,666.67 + (299/300 × 500,000) × 0.00407 = 3,696.94

At the end of the second month, the debt is reduced to 298/300ths of its original value.

\(B_{2}\) = 298/300 × 500,000 = $496,667

Fast forward 30 years and you will only owe 1/300th of $500,000

\(B_{299}\) = 1/300 × 500,000 = $1,666.67

during the last month of your mortgage. You will pay a correspondingly very small amount of interest on your debt then, only 0.00407 × $1,666.67 = $6.79. Your final payment will be

1,666.67 + 6.79 = 1,673.46

Notice that the amount of interest paid on the first month is 300 times larger than the amount of interest paid on the last month! This large difference makes this scheme impractical for many people who can easily afford the final payments but not the initial ones.

In this decreasing payments scheme, the monthly payments decrease linearly by

0.00407 × 1,666.67 = $6.79 per month.

Simply adding up all the payments shows that you will end up paying a total of $806,579 on $500,000 of debt. In other words, 1.613 times the original amount.

Interest paid through Fixed Payments

Most mortgages are paid through fixed (rather than decreasing) monthly payments.

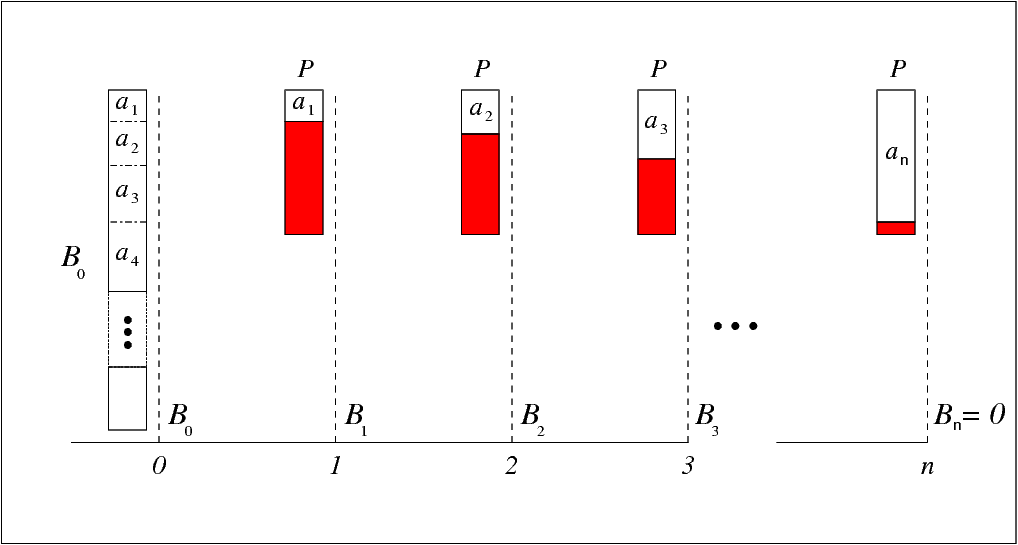

In a fixed-payments mortgage, the home owner borrows an initial amount \( B_0 \) from the bank and makes a total of \(n\) fixed monthly payments of \(P\) dollars to pay off his debt. As the home owner makes his payments, the remaining balance decreases and a progressively smaller fraction of each payment goes towards paying interest. Consequently, more and more money goes towards paying the principal. This is shown in the figure below.

The red areas depict how much interest is being paid each month and the \(a_k\) represent the corresponding amount of principal being paid on the k-th month. The remaining balance after the k-th payment is \(B_k\). After the home owner makes his last payment this balance is zero.

Let us calculate what the monthly payments should be. Instead of using the interest rate \(i\), we will use the gross interest rate given by \(r=1+i\) to simplify the calculation. For the monthly rate in our example above \(i=0.00407\) and \(r=1.00407\).

The initial balance is \(B_0\). After the first month, the remaining balance will be

\[B_1 = r B_0 - P\]The balance at the end of the second month is

\[\begin{align} B_2 & = r B_1 - P \\ & = r ( r B_0 - P) - P \\ & = r^2 B_0 - r P - P \end{align}\]At the end of the third month

\[\begin{align} B_3 & = r B_2 - P \\ & = r ( r B_1 - P) - P \\ & = r ( r ( r B_0 - P ) - P) - P \\ & = r^3 B_0 - r^2 P - r P - P \end{align}\]In short, after each month the remaining balance is being multiplied by the gross interest rate \(r\) and then a payment of \(P\) is subtracted. At the end of \(n\) months the home owner will have paid his mortgage and we will have

\( 0 = B_n = r^n B_0 -r^{n-1} P - r^{n-2} P - \ldots - r P - P \)

\( 0 = r^n B_0 - P ( r^{n-1} + r^{n-2} + \ldots + r + 1) \)

Calculating the sum for the standard geometric progression on the right we obtain.

\[ 0 = r^n B_0 - P \frac{r^n - 1}{r - 1} \]

Finally, rearranging the formula for \(P\)

\[ P = B_0 \frac{r^n(r - 1)}{r^n - 1}\]

This formula is all we need to calculate how much your monthly payments should be. For our $500,000 loan with 5% yearly interest we obtain that \(P\) = $2890.69. Simply adding up all 300 payments shows that you will pay a total of $867,207 which is 1.73 times the borrowed amount. Put it another way, each payment is 73% larger, an extra 2890.69 - 1666.67 = $1224.02, than it would be for a zero interest rate loan.

We left out the very important tax breaks. The U.S. government gives a tax break for interest paid on mortgages. If we assume that the home owner is in a 33% tax bracket and can benefit from both federal and state tax incentives. The amount paid in interest is reduced by 2/3. In our example, this means that only \(\frac{2}{3}\) × 1224.02 = $816.01 is flushed down the toilet each month. Add to this amount the extra costs of owning a home and compare the total to your rent payments. If you are still paying more than the total in rent and you don’t expect home prices to fall, buying a home may be a good move for you.

Conclusion

Don’t fool yourself into thinking buying a home is always a good investment because you will not be paying rent. Calculate how much interest you will be paying, what tax breaks you will get, the extra costs of owning a property (recurring property tax, insurance, maintenance and depreciation and the one-time costs of closing a deal) add the opportunity cost of not having savings and compare tall hat to your rent payments before making a decision. The $816 dollars above only take into account the interest itself.

This entry has been updated to include the opportunity cost and make explicit that the calculation above does not include all costs. The layout has also been changed.