Generating random integers from random bytes

Here is a problem that appears simpler than it is. Programmers many times have at their disposal a source of random bits but need to generate uniformly distributed random integers in a given range. The immediate algorithms for doing this, using remainders or scaling lead to biased distributions. A cursory review of open source software shows that using these is a common problem. They even show up in cryptographic libraries! Usually with minor effects. If you want to learn how to do this “conversion” properly, read on.

Imagine you are running a simple lottery that works like a raffle. All the tickets are sold at the same price. People buy tickets throughout the week and a single winning ticket is announced at the end of the week. There is a winner every week; the total prize does not accumulate week-to-week.

A basic requirement for this lottery is that every ticket must have the same chance of winning as every other ticket. In fact, this may be a legal requirement. It is not fair for a ticket to have a higher chance of winning than any other ticket as they all cost the same.

The number of people buying tickets changes from week to week; but no matter how many tickets are sold, the lottery must always be fair. Each week, the wining ticket must be drawn from a uniform distribution over all the tickets sold. You don’t want to break the law.

To aid you in executing the lottery you are given a perfect source of random bytes. Imagine that by using some oscillators, heat and quantum wizardry Intel has just release a wonderful new chip. This chip will give you as many random bits as you want. Each bit is drawn from a Bernoulli distribution with probability \(\frac{1}{2}\). In the javascript world, this is equivalent to a perfect version of getRandomValues() or Node.js’ randomBytes().

Armed with your perfect source of random bits you set out to code the software that will draw the winning lottery ticket. Here are a few ways not to do it.

Bias from Remainders

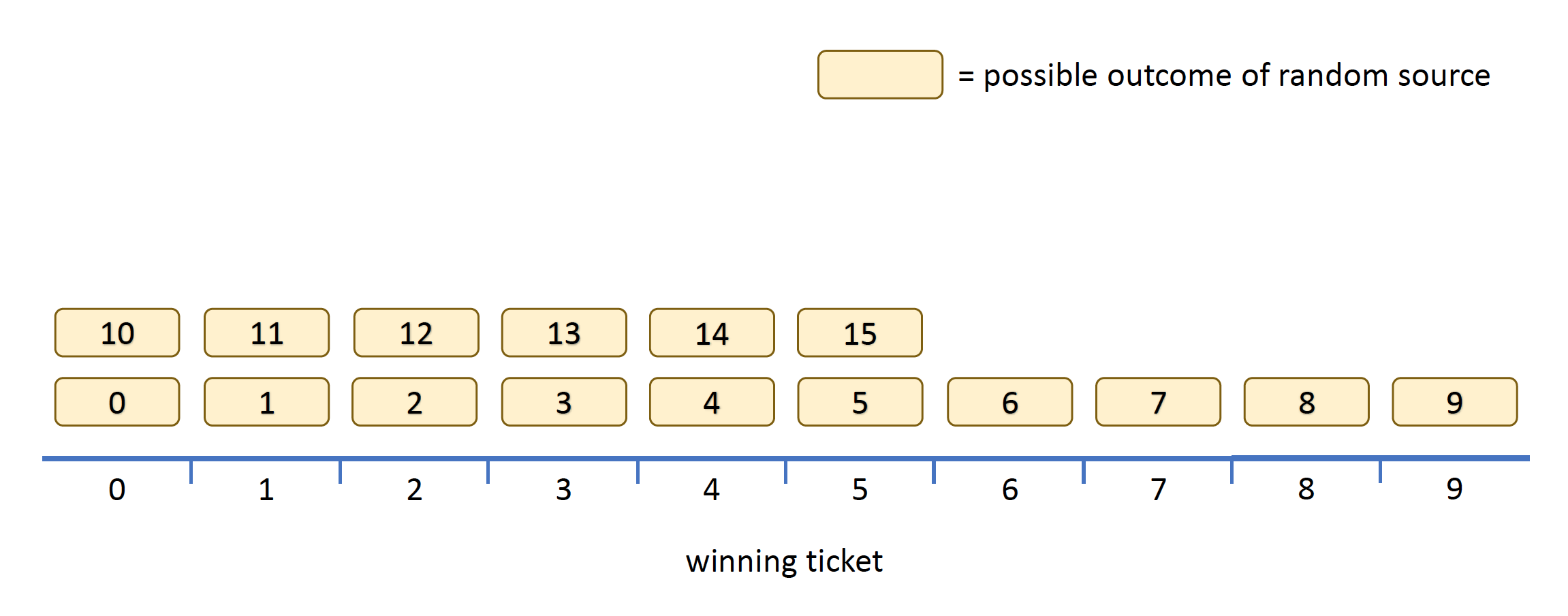

Assume that in a given week \(N=10\) tickets were sold. Using our source of randomness we use the next power of 2, that is 16, and pick a random number between 0 and 15 by using 4 perfectly random bits. We then proceed to calculate the winning ticket using simple modular arithmetic.

"use strict";

const crypto = require('crypto')

/* use just 4 random bits - a value from 0 to 15 */

const randomBits = crypto.randomBytes(1).readUInt8() & 0x0F

const N = 10

let winner = randomBits % N

console.log(`And the winner is ticket number ${winner} !`)

Unfortunately, this generates a biased distribution because \(N\) is not a power of 2. We will be grouping the 16 values that can be returned by randomBytes into 10 “equivalence classes”. Some classes will collect more values than others, as the next diagram shows.

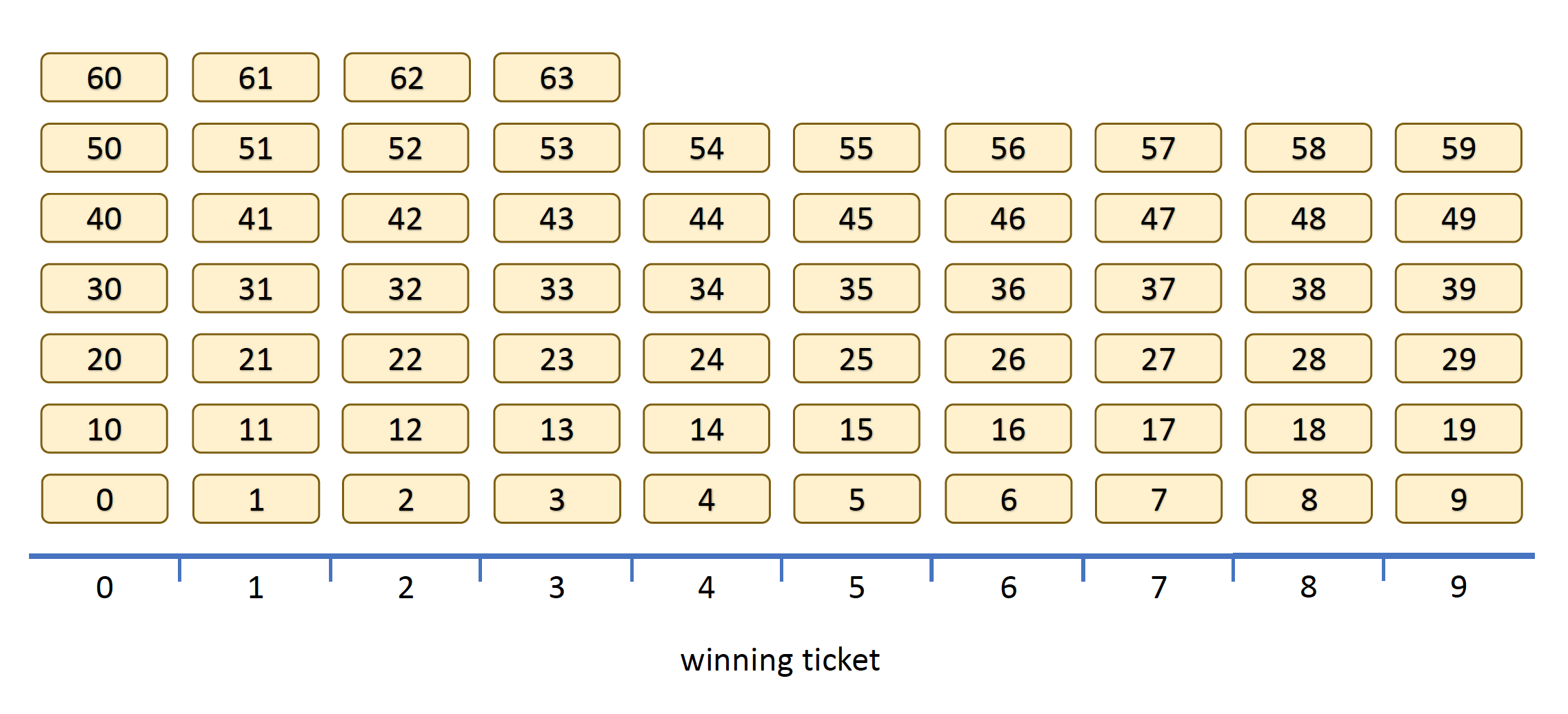

This is really bad for the lottery as tickets 0 through 5 are twice as likely to win as the other tickets. We can mitigate this problem by using more random bits. If we use 6 random bits to pick a number between 0 and 63 and then apply the modulus (i.e. %) operation, we have the following situation:

Two points to note:

- Because \(N = 10\) is not a power of 2, there will always be some favored tickets that are more likely to win.

- The discrepancy between the most likely and the least likely tickets is a function of the number of random bits used. If we use \(m\) random bits (we used \(m = 6\) in the last diagram), the difference in probability between the more likely and least likely tickets is \(1/2^m\).

The second point above means that we can make the unfairness imperceptibly small by using lots of random bits. This is good. However, the difference in probability never actually goes away. We will never generate a truly uniform distribution this way.

Bias from Scaling

Another attempt at generating a uniform distribution goes like this. Imagine we have a random number \(r\) in the interval \([0,1)\). We can multiply \(r\) by the number of tickets sold \(N = 10 \) to obtain a random number \(r N\) in the interval \([0,10)\) and then just take the integer part.

This mistaken algorithm is used a lot in javascript because the output of Math.random looks a lot like the random number \(r\). Here’s what it would look like in Node.js code:

"use strict";

/* get random number in [0,1) */

const r = Math.random()

const N = 10

let winner = Math.floor(r * N)

console.log(`And the winner is ticket number ${winner} !`)

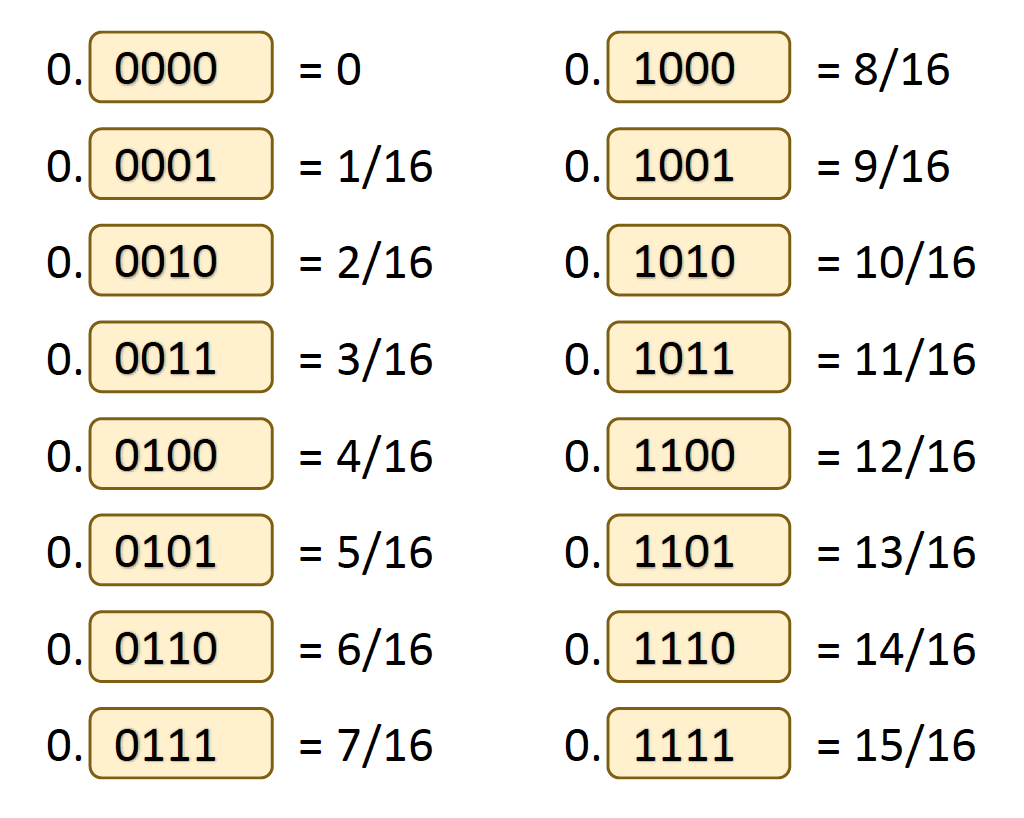

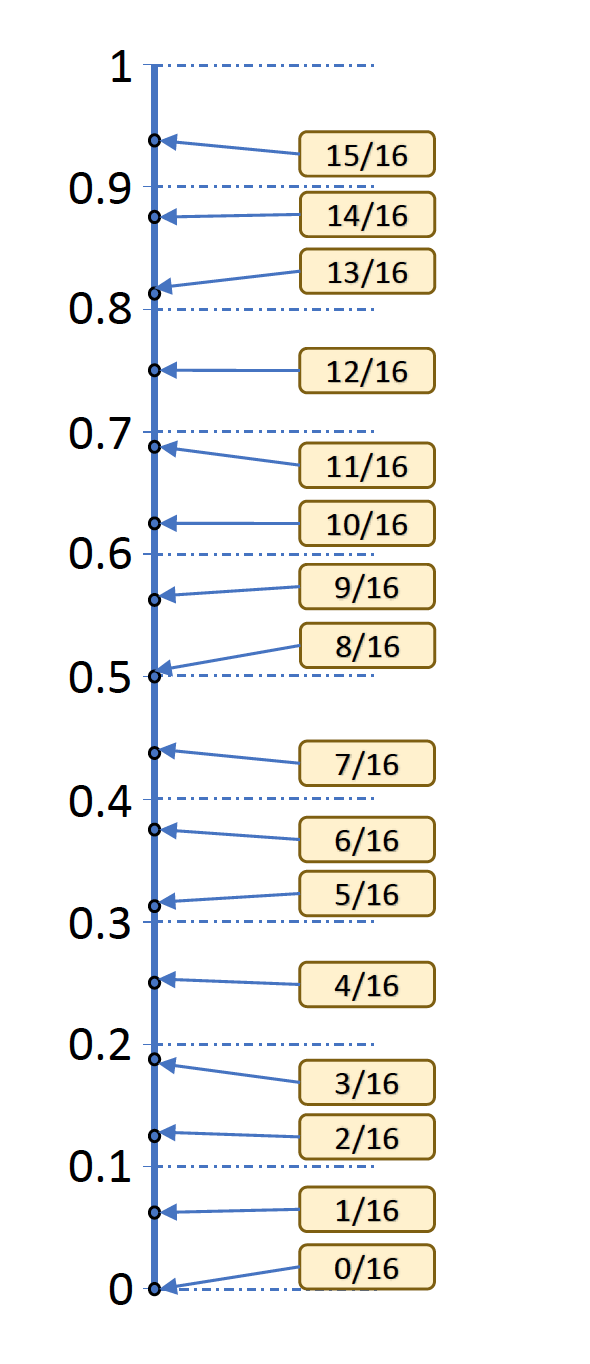

Unfortunately, this idea also generates a biased distribution. This is because we don’t actually have a random number \(r\) in the interval \([0,1)\). All we have are random bits. We would need an infinite number of random bits to be able to generate a random number in \([0,1)\). Because we do not have an infinite number of bits, the best we can do is to approximate \(r\) and this approximation leads to the bias. To see why, first consider using 4 bits to generate a random number in \([0,1)\). This can be done by sticking a “0.” in front of the bits generated and reading them as a binary number. This is equivalent to dividing the output of 4 bits by \(16=2^4\) as shown below.

These are the possible values that we can generate inside the \([0,1)\) interval with only 4 random bits. Now consider what will happens in the expression Math.floor(r * N) for \(N = 10 \). Any value of \(r\) smaller than 0.1 will be floored to zero. Similarly, values of \(r\) in the range \([0.1 , 0.2)\) will be output as 1, values in the range \([0.2 , 0.3)\) will be output as 2, and so on. In short, this function partitions the \([0,1)\) interval into 10 distinct regions. Unfortunately, we have a different number of possible inputs falling in each region as the next diagram shows.

This asymmetry makes some outputs more likely than others. For example, zero which corresponds to values in the region \([0 , 0.1)\) is twice as likely as 2 which corresponds to the region \([0.2 , 0.3)\)). Again, this happens because some regions or “equivalence classes” contain more possible input values. Each equivalence class corresponds to a lottery ticket, so some lottery tickets are more likely to win.

Unless \(N\) is a power of 2, this will always happen. Just like in the case of remainder bias, we can mitigate the problem by using a large number of bits. If we use a standard 53 bits, the difference in probability between the most likely and the least likely tickets will be \(2^{-53}\approx \frac{1}{10^{16}}\). That is virtually undetectable and good for most (non-cryptographic) applications, but this is not a truly uniform distribution. We can do better.

Warning: The trick of using more random bits to obtain a smaller bias works if we don’t also have to increase the number of equivalence classes \(N\), otherwise we might be back where we started.

Doing it right — Rejection Sampling

There is, in fact, a simple way to generate our winning ticket from a perfectly uniform (i.e. 100% fair) distribution. We sample our source of random bits and then simply reject samples we don’t like.

For example, we use our perfect source of random bits to generate an integer and simply reject samples outside our range. We can generate an integer between 0 and 15 using 4 bits of our perfect source. If the output is smaller than 10 then it is accepted; otherwise, it is rejected and we try again. Here’s what it looks like in code:

"use strict";

const crypto = require('crypto')

function sample(){return crypto.randomBytes(1).readUInt8() & 0x0F}

const N = 10

/* Rejection Sampling */

var s

do {

s = sample() // s is a value from 0 to 15

} while (s >= N) // reject if outside our desired range

let winner = s

console.log(`And the winner is ticket number ${winner} !`)

Our source of randomness is perfect, so rejecting out of bounds samples will not bias the samples that are allowed through. However, there is something slightly troubling about this algorithm. It may never terminate! The random source may continually output random bits whose value is larger than 9 forcing us to sample forever. This is highly unlikely as our source is random, but we cannot set a hard worst-case bound on how long this algorithm will run.

This is a trade-off we face, in the previous biased-distribution examples we could guarantee that our algorithms would terminate, but had to use more and more bits to make the bias in the generated probability distributions small. With rejection sampling, we guarantee that there is no bias in the generated probability distribution, but we may have to use more and more bits to ensure our algorithm terminates.

Termination

When one does have a good source of randomness, it is easy to ensure “timely” termination. It will be extremely unlikely that the rejection sampling algorithm will have to sample many times to be able to produce a valid sample. More precisely, the likelihood that \(k \) samples are needed before a valid sample is found decreases exponentially as \(k \) increases and is smaller than \(2^{-k}\). We just have to ensure that the probability that any single sample is accepted is at least \(1/2\).

Consider our running example. There is a \(10/16 = 5/8\) chance that one sample will fall in our desired range. In other words, there is a \(3/8\) chance that it will be rejected. What is the likelihood that we have to try 10 or more samples to get one in the desired range?

We only try 10 or more samples if on the previous 9 attempts we got a sample that was larger than 9. As the samples are independent, that is going to happen with probability \( (\frac{3}{8})^9 \approx 0.00015 \). This is once every 6818 runs. The probability we will need more than 50 samples is a minuscule \(5 \times 10^{-22} \).

In the previous example, we only used 4 bits of randomness to generate an integer from 0 to 15. If we had used 32 bits from our random source to obtain a number between 0 and \( 2^{32} - 1 = 4294967295 \) and rejected all samples larger than 10, we would have a problem because we would be rejecting most of the samples. In this case, the probability we will have to sample at least 10 times becomes \( ( \frac{2^{32}-10}{2^{32}})^9 \approx 0.99999998 \). And the probability we will need more than 50 samples becomes 0.99999988. In other words, we will most likely be sampling more than 50 times every time we run our algorithm. This is definitely not what we want.

Extending our range

The problem with using 32 bits as above is that we rejected too many samples. The probability of finding an acceptable sample was too low. Again, we have to ensure that the probability that any single sample is accepted is at least \(1/2\).

Consider the simpler example of using 8 bits, that is a number between 0 and 255 to obtain a lottery winner \(N = 10\). Instead of rejecting all samples equal to 10 or above, we calculate the largest multiple of 10 that is less than \(2^8\). That number is 250. We then only reject values at or above this number. Obviously, if we do this we will get a number between 0 and 250, which is not what we want. But because 250 is an exact multiple of 10, we can now safely apply the remainder to get a number in the desired range without biasing our perfectly uniform distribution.

Here’s the code:

"use strict";

const crypto = require('crypto')

function sample(){return crypto.randomBytes(1).readUInt8()}

const maxRange = 256

const N = 10

/* extended range rejection sampling */

const q = Math.floor( maxRange / N )

const multiple_of_N = q * N

var s

do {

s = sample() // 0 to 255

} while (s >= multiple_of_N) // extended acceptance range

let winner = s % N

console.log(`And the winner is ticket number ${winner} !`)

Furthermore, the probability each sample is accepted is \( \frac{250}{256} \) and that is larger than \( \frac{1}{2} \) as we wanted.

We also need to make sure we have more random bits than the range of integers we need.

Polishing up

We have assumed, so far, that we have a perfect source of random bits. This gave us assurance that our algorithm will (with high probability) eventually be done. However, if we have a buggy or biased source of randomness, our rejection sampling algorithm can go into an infinite loop by rejecting all samples. This should never happen with a truly random source. Actually, never is a strong word, let’s just say it should not happen in the next billion years. So, we want to signal there is an error when this happens, rather than go into an infinite loop.

The final version of our algorithm sets an upper bound on how many times sampling is attempted before a valid sample is found. We will set this upper bound to be 100 attempts. The probability that we need more than 100 random samples is less than \( 2^{-100} \), so it is more likely we have a bug in our source of randomness than that this long sequence of rejected samples actually happened by chance.

We also provide a simple utility function getRandIntInclusive to generate integers in an arbitrary range that includes the upper and lower bounds. We also made everything work sensibly when those bounds are fractional numbers: it works as long as there is an integer in the range. So that,

getRandIntInclusive(2, 3)returns 2 or 3;getRandIntInclusive(2.1, 2.9)fails; andgetRandIntInclusive(2.1, 3.9)always returns 3.

Here’s the final version:

"use strict";

const crypto = require('crypto')

// 32 bit maximum

const maxRange = 4294967296 // 2^32

function getRandSample(){return crypto.randomBytes(4).readUInt32LE()} //Node.js, change for Web API

function unsafeCoerce(sample, range){return sample % range}

function inExtendedRange(sample, range){return sample < Math.floor(maxRange / range) * range}

/* extended range rejection sampling */

const maxIter = 100

function rejectionSampling(range, inRange, coerce){

var sample

var i = 0

do{

sample = getRandSample()

if (i >= maxIter){

// do some error reporting.

console.log("Too many iterations. Check your source of randomness.")

break /* just returns biased sample using remainder */}

i++

} while ( !inRange(sample, range) )

return coerce(sample, range)

}

// returns random value in interval [0,range) -- excludes the upper bound

function getRandIntLessThan(range){

return rejectionSampling(Math.ceil(range), inExtendedRange, unsafeCoerce)}

// returned value is in interval [low, high] -- upper bound is included

function getRandIntInclusive(low, hi){

if (low <= hi) {

const l = Math.ceil(low) //make also work for fractional arguments

const h = Math.floor(hi) //there must be an integer in the interval

return (l + getRandIntLessThan( h - l + 1)) }}

var winner = getRandIntInclusive(0, 9)

console.log(`And the winner is You! Ticket number ${winner} !`)

(Here’s a haskell version of the same code.)

That’s all folks! Now, you know how to properly generate uniformly distributed random integers from random bytes. Tricky, isn’t it!?

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Tikhon Jelvis for some great suggestions to improve this blog post.